Medical tourism and policy implications for health systems: a conceptual framework from a comparative study of Thailand, Singapore and Malaysia

Medical tourism is a growing phenomenon with policy implications for health systems, particularly of destination countries. Private actors and governments in Southeast Asia are promoting the medical tourist industry, but the potential impact on health systems, particularly in terms of equity in access and availability for local consumers, is unclear. This article presents a conceptual framework that outlines the policy implications of medical tourism's growth for health systems, drawing on the cases of Thailand, Singapore and Malaysia, three regional hubs for medical tourism, via an extensive review of academic and grey literature. Variables for further analysis of the potential impact of medical tourism on health systems are also identified. The framework can provide a basis for empirical, in country studies weighing the benefits and disadvantages of medical tourism for health systems. The policy implications described are of particular relevance for policymakers and industry practitioners in other Southeast Asian countries with similar health systems where governments have expressed interest in facilitating the growth of the medical tourist industry. This article calls for a universal definition of medical tourism and medical tourists to be enunciated, as well as concerted data collection efforts, to be undertaken prior to any meaningful empirical analysis of medical tourism's impact on health systems.

Introduction

Growing demand for health services is a global phenomenon, linked to economic development that generates rising incomes and education. Demographic change, especially population ageing and older people's requirements for more medical services, coupled with epidemiological change, i.e. rising incidence of chronic conditions, also fuel demand for more and better health services. Waiting times and/or the increasing cost of health services at home, coupled with the availability of cheaper alternatives in developing countries, has lead new healthcare consumers, or medical tourists, to seek treatment overseas [1]. The correspondent growth in the global health service sector reflects this demand. The globalisation of healthcare is marked by increasing international trade in health products and services, strikingly via cross border patient flows.

In Southeast Asia, the health sector is expanding rapidly, attributable to rapid growth of the private sector and notably, medical tourism, which is emerging as a lucrative business opportunity. Countries here are capitalising on their popularity as tourist destinations by combining high quality medical services at competitive prices with tourist packages. Some countries are establishing comparative advantages in service provision based on their health system's organizational structure (table 1). Thailand has established a niche for cosmetic surgery and sex change operations, whilst Singapore is attracting patients at the high end of the market for advanced treatments like cardiovascular, neurological surgery and stem cell therapy [2]. In Singapore, Malaysia and Thailand alone, an estimated 2 million medical travellers visited in 2006 - 7, earning these countries over US$ 3 billion in treatment costs (table 2).

The framework facilitated the identification of the following variables for empirical analysis:

Governance: the number and content of GATs health sector commitments, the number and size of medical tourist government committees or agencies, availability of medical tourist visa.

Delivery: number of hospitals in public and private sector treating foreign patients, consumption of health services by domestic and foreign population (hospital admissions).

Financing: medical tourist revenues, type of medical tourist payment (service fee or insurance, level of copayment), foreign direct investment in the health sector.

Human resources: doctor and nurse ratios per 1000 population, proportion of specialists in the public and private sectors, number of specialists treating foreign patients.

Regulation: number of JCI accredited hospitals, number of medical tourist visits facilitated by brokers.

At present there is an acute lack of reliable empirical data concerning medical tourist flows. Most urgently, a universal definition of who counts as a medical tourist (e.g. per procedure or per inpatient) should be agreed on, ideally at the international (WHO) or regional level (amongst Ministries of Health, Trade, Tourism and private hospital associations). Variation in definitions and estimates amongst the three study countries alone are significant. Singapore's Tourism Board estimates medical tourist inflows based on tourist exit interviews with a small sample population, whilst the Association of Private Hospitals in Malaysia collects data only from member hospitals and includes all foreign patients, including foreign residents and those who happen to require medical care whilst on vacation [28]. Thailand's Ministry of Commerce collects data on medical tourist inflows from private hospitals, counting foreign patients as the APHM does, except that definitions between hospitals about numbers vary (some count inpatient admissions, others per procedure) [71]. Standardised data collection will enable researchers to make meaningful cross country comparisons, as well as carry out detailed country specific studies to investigate the benefits and disadvantages of medical tourism's impact on health systems.

Conclusion

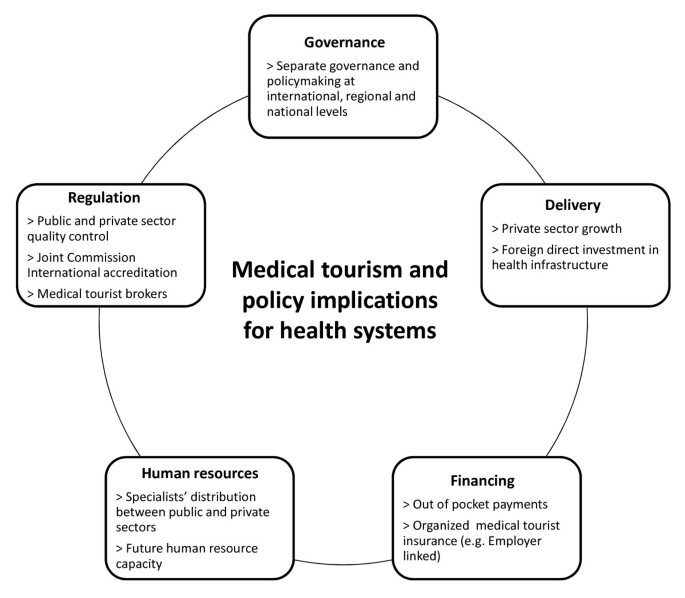

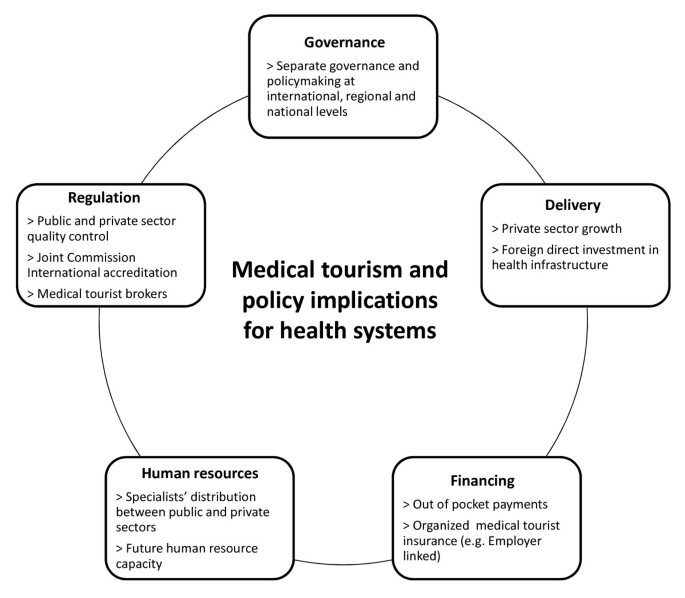

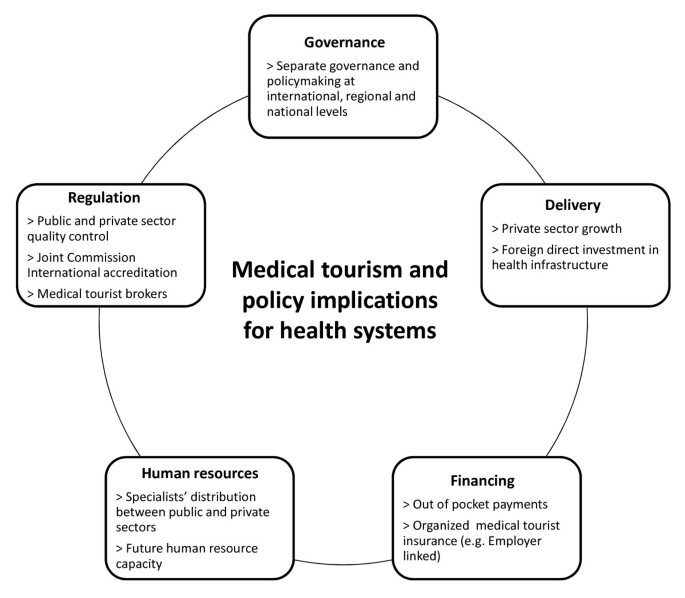

The rise of medical tourism in Thailand, Singapore and Malaysia and governments' endorsement of the trend has raised concerns about its potential impact on health systems, namely the exacerbation of existing inequitable resource distribution between the public and private sectors. Nowhere is this more evident than in Southeast Asia, where regulation and corrective policy measures have not kept pace with rapid private sector growth during the past few decades. This paper presents a conceptual framework (Figure 1) that identifies the policy implications of medical tourism for health systems, from a comparative analysis of Thailand, Singapore and Malaysia. This framework can provide a basis for more detailed country specific studies, of particular use for policymakers and industry practitioners in other Southeast Asian countries where governments have expressed an interest in facilitating the development of the industry. Medical tourism can bring economic benefits to countries, including additional resources for investment in healthcare. However, unless properly managed and regulated on the policy side, the financial benefits of medical tourism for health systems may come at the expense of access to and use of health services by local consumers. Governments and industry players would do well to remember that health is wealth for both foreign and local populations.

References

- Hazarika I: Medical tourism: its potential impact on the health workforce and health systems in India. Health Policy and Planning. 2010, 25: 248-251. 10.1093/heapol/czp050. ArticlePubMedGoogle Scholar

- UNESCAP: Medical travel in Asia and the Pacific: challenges and opportunities. 2007, Thailand, United Nations Economic and Social Commission for Asia and the Pacific, Accessed 29-09-2010, [http://www.unescap.org/ESID/hds/lastestadd/MedicalTourismReport09.pdf] Google Scholar

- Chongsuvivatwong V, Phua KH, Yap MT, Pocock NS, Hashim JH, Chhem R, Wilopo SA, Lopez AD: Health and health-care systems in southeast Asia: diversity and transitions. Lancet. 2011, 377 (9763): 429-37. 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)61507-3. ArticlePubMedGoogle Scholar

- Tourism Malaysia: Media info: Health tourism in Malaysia. 2008, Communications and Publicity Division, Tourism Malaysia, Accessed 29-9-2010, [http://www.tourism.gov.my/corporate/images/media/features/Health%20Tourism%20Oct%202008.pdf] Google Scholar

- Singapore Medicine: Media Factsheet: Singapore, more than just a world class healthcare destination. 2010, Singapore Medicine Google Scholar

- Carrera P, Bridges J: Health and medical tourism: what they mean and imply for health care systems. Health and Ageing. 2006, The Geneva Association, 15: Google Scholar

- Carrera P, Bridges J: Globalization and healthcare: understanding health and medical tourism. Expert Review of Pharmacoeconomics and Outcomes Research. 2006, 6 (Suppl 4): 447-454. ArticlePubMedGoogle Scholar

- Chee HL: Medical tourism in Malaysia: international movement of healthcare consumers and the commodification of healthcare. Asia Research Institute, National University of Singapore, submitted. 2007, Accessed 04-03-2011 Google Scholar

- Whittaker A, Manderson L, Cartwright E: Patients without borders: understanding medical travel. Medical Anthropology. 2010, 29 (4): 336-343. 10.1080/01459740.2010.501318. ArticlePubMedGoogle Scholar

- Smith R, Chanda R, Tangcharoensathien V: Trade in health related services. Lancet. 2009, 373: 593-601. 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)61778-X. ArticlePubMedGoogle Scholar

- Blouin C, Chopra M, Van Der Hoeven R: Trade and social determinants of health. Lancet. 2009, 373: 502-507. 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)61777-8. ArticlePubMedGoogle Scholar

- Chanda R: Trade in health services. Bulletin of the World Health Organisation. 2002, 80: 158-163. Google Scholar

- Hopkins K, Labonte R, Runnels V, Packer C: Medical tourism today: what is the state of existing nowledge?. Journal of Public Health Policy. 2010, 31 (2): 185-198. 10.1057/jphp.2010.10. ArticlePubMedGoogle Scholar

- Chee HL: Ownership, control and contention: challenges for the future of healthcare in Malaysia. Social Science and Medicine. 2008, 66: 2145-2156. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2008.01.036. ArticlePubMedGoogle Scholar

- Pachanee C, Wibulpolprasert S: Incoherent policies on universal coverage of health insurance and promotion of international trade in health services in Thailand. Health Policy and Planning. 2006, 21 (4): 310-318. 10.1093/heapol/czl017. ArticlePubMedGoogle Scholar

- Wibulpolprasert S, Pengpaibon P: Integrated strategies to tackle the inequitable distribution of doctors in Thailand: four decades of experience. Human Resources for Health. 2003, 1 (12): Accessed 04-03-2011, [http://www.human-resources-health.com/content/1/1/12] Google Scholar

- Turner L: First world health care at third world prices: globalization, bioethics and medical tourism. Biosocieties. 2007, 2: 303-325. 10.1017/S1745855207005765. ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Blouin C: Trade in health services: can it improve access to health care for poor people?. Global Social Policy. 2010, 10 (3): 293-295. 10.1177/14680181100100030202. ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Connell J: Medical tourism: sea, sun sand and . surgery. Tourism Management. 2006, 27: 1093-1100. 10.1016/j.tourman.2005.11.005. ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Garcia Altes A: The development of health tourism services. Annals of Tourism Research. 2005, 32 (1): 262-66. ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Henderson JC: Healthcare tourism in Southeast Asia. Tourism Review International. 2004, 7: 111-121. ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Heung VCS, Kucukusta D, Song H: A conceptual model of medical tourism: implications for future research. Journal of Travel and Tourism Marketing. 2010, 27: 336-251. ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Fidler DP, Drager N, Lee K: Managing the pursuit of health and wealth: the key challenges. Lancet. 2009, 373: 325-31. 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)61775-4. ArticlePubMedPubMed CentralGoogle Scholar

- Lee K, Sridhar D, Patel M: Bridging the divide: global governance of trade and health. Lancet. 2009, 373: 416-22. 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)61776-6. ArticlePubMedPubMed CentralGoogle Scholar

- Arunanondchai J, Fink C: Trade in health services in the ASEAN region. Health Promotion International. 2007, 21 (Suppl 1): 59-66. Google Scholar

- Diaz Benavides D: Trade policies and export of health services: a development perspective. Trade in Health Services, Global, Regional and Country Perspectives. 2002, Washington DC: Pan American Health Organization, Program on Public Policy and Health, Division of Health and Human Development, 53-69. Google Scholar

- Cohen G: Protecting patients with passports: medical tourism and the patient protective argument. Harvard Law School Public Law and Legal Theory Working Paper. 2010, 10-08: Google Scholar

- Chee HL: Medical tourism and the state in Malaysia and Singapore. Global Social Policy. 2010, 10 (3): 336-357. 10.1177/1468018110379978. ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Forgione D, Smith P: Medical tourism and its impact on the US health care system. J Health Care Finance. 2006, 34 (1): 27-35. Google Scholar

- Pennings G: Ethics without boundaries: medical tourism. Principles of health care ethics. Edited by: Ashcroft RE, Dawson A, Draper H, McMillan JR. 2007, Chicester: John Wiley and Sons, 505-510. 2 Google Scholar

- Atun R, De Jongh T, Secci F, Ohiri K, Adeyi O: Integration of targeted health interventions into health systems: a conceptual framework for analysis. Health Policy and Planning. 2010, 25: 104-111. 10.1093/heapol/czp055. ArticlePubMedGoogle Scholar

- Badara S, Evans T, Dybul M, Atun R, Moatti JP, Nishtar S, Wright A, Celletti F, Hsu J, Kim JY, Brugha R, Russell S, Etienne C: An assessment of interactions between global health initiatives and country health systems. Lancet. 2009, 373: 2137-69. ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Hsiao W: What is a health system? Why should we care?. Harvard School of Public Health, working paper. 2003 Google Scholar

- Marmor T, Freeman R, Okma K: Comparative perspectives and policy learning in the world of health care. Journal of Comparative Policy Analysis. 2005, 7 (4): 331-348. 10.1080/13876980500319253. ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Punch K: Introduction to social research: quantitative and qualitative approaches. 2005, London: Sage, 2 Google Scholar

- Glaser BG, Strauss AL: The discovery of Grounded Theory: strategies for qualitative research. 1967, New York: Adline Publishing Google Scholar

- Zeigler D: International trade agreements challenge tobacco and alcohol control policies. Drug and Alcohol Review. 2006, 25: 567-579. 10.1080/09595230600944495. ArticlePubMedGoogle Scholar

- WTO GATs services database. Accessed 10-2-2011, [http://tsdb.wto.org/default.aspx]

- WTO GATs introduction. Accessed 10-2-2011, [http://www.wto.org/english/tratop_e/serv_e/gats_factfiction1_e.htm]

- ASEAN: ASEAN cooperation in trade in services. 2000, ASEAN Google Scholar

- Hew D, Soesastro H: Realizing the ASEAN economic community by 2020: ISEAS and ASEAN - ISIS approaches. ASEAN Economic Bulletin, Institute of Southeast Asian Studies. 2003 Google Scholar

- ASEAN: ASEAN annual report 2009 - 2010: Bridging markets, connecting peoples. 2010, ASEAN Google Scholar

- ASEAN: Joint statement of the 10 th ASEAN health ministers meeting: "healthy people, healthy ASEAN". Singapore. 2010 Google Scholar

- Huang R: Khazanah controls 95% of healthcare firm Parkway Holdings. 2010, Channel News Asia Google Scholar

- MOH Malaysia: Strategic plan 2006 - 2010. 2008, Ministry of Health Malaysia Google Scholar

- MTI Singapore: Developing Singapore as a compelling hub for healthcare services in Asia. 2002, Health Sector Working Group, Ministry of Trade and Industry Singapore Google Scholar

- MOH Singapore: Roles and priorities. 2008, Ministry of Health Singapore, Accessed 14-7-2010, [http://www.moh.gov.sg/mohcorp/about.aspx?id=116] Google Scholar

- MOH Thailand: Thailand health profile report 2005 - 2007. 2007, Ministry of Health Thailand, Accessed 14-7-2010, [http://www.moph.go.th/ops/thp/index.php?option=com_content&task=view&id=6&Itemid=2] Google Scholar

- SingStat: Yearbook of Statistics 2009. 2009, Singapore Department of Statistics Google Scholar

- Arunanondchai J, Fink C: Trade in health services in the ASEAN region. World Bank Policy Research Working Paper. 2007, 4147: Google Scholar

- O'Donnell O, Doorslaer E, Rannan-Eliya RP, Somanathan A, Adhikari SR, Harbianto D, Garg CC, Hanvoravongchai P, Huq MN, Karan A, Leung GM, Ng CW, Pande BR, Tin K, Tisayaticom K, Trisnantoro L, Zhang Y, Zhao Y: The incidence of public spending on healthcare: comparative evidence from Asia. World Bank Economic Review. 2007, 21 (1): 93-123. 10.1093/wber/lhl009. ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Tangcharoensathien V, Patcharanarumol W, Ir P, Aljunid SM, Mukti AG, Akkhavong K, Banzon E, Huong DB, Thabrany H, Mills A: Health-financing reforms in southeast Asia: challenges in achieving universal coverage. Lancet. 2011, 377 (9768): 863-873. 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)61890-9. ArticlePubMedGoogle Scholar

- WHO: Global Health Observatory. Accessed 20-01-2011, [http://apps.who.int/ghodata/]

- MOH Malaysia: Health facts 2008. 2009, Health Informatics Centre, Planning and Development Division, Ministry of Health Malaysia Google Scholar

- National Statistical Office of Thailand: The 2007 private hospital survey. 2007, Ministry of Information and Community Technology Google Scholar

- Ramesh M, Xun W: Realigning public and private health care in Southeast Asia. The Pacific Review. 2008, 21 (2): 171-187. 10.1080/09512740801990238. ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Phua KH: Attacking hospital performance on two fronts: network corporatization and financing reforms in Singapore. Innovations in health service delivery: the corporatization of public hospitals. Edited by: Preker AS, Harding A. 2003, Washington DC: Health, Nutrition and Population Series World Bank, 451-485. Google Scholar

- Joint Commission International: Accredited organizations. Accessed 20-01-2011, [http://www.jointcommissioninternational.org/jci-accredited-organizations/]

- Hirschman AO: Exit, Voice, and Loyalty: Responses to Decline in Firms, Organizations, and States. 1970, Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press Google Scholar

- Ministry of Finance Malaysia, Employees Provident Fund. Accessed 20-01-2011, [http://www.kwsp.gov.my/index.php]

- Phua KH: Health care financing reforms in the Asia-Pacific region. Public Administration and Policy. 2003, 12 (1): 13-36. Google Scholar

- Phua KH, Chew AH: Towards a comparative analysis of health system reforms in the Asia - Pacific region. Asia Pacific Journal of Public Health. 2002, 14 (1): 9-16. ArticlePubMedGoogle Scholar

- MOH Singapore: Medisave for approved overseas hospitalization. 2010, MOH press release Google Scholar

- Deloitte Center for Health Solutions: Medical tourism: update and implications. Deloitte. 2009, Accessed 20 - 1 - 2011, [http://www.deloitte.com/us/medicaltourism] Google Scholar

- Hughes D, Leethongdee S: Universal coverage in the land of smiles: lessons from Thailand's 30 baht health reforms. Health Affairs. 2007, 26: 999-1008. 10.1377/hlthaff.26.4.999. ArticlePubMedGoogle Scholar

- WHO: World health report 2006. 2006, Geneva, Switzerland Google Scholar

- Kanchanachitra C, Lindelow M, Johnston T, Hanvoravongchai P, Lorenzo FM, Huong NL, Wilopo SA, De la Rosa JF: Human resources for health in southeast Asia: shortages, distributional challenges, and international trade in health services. Lancet. 2011, 377 (9767): 769-781. 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)62035-1. ArticlePubMedGoogle Scholar

- Bhargava A, Docquier F, Moullan Y: New medical brain drain data set. 2010, Accessed 10-2-2011, [http://perso.uclouvain.be/frederic.docquier/oxlight.htm] Google Scholar

- WHO: World health statistics 2009. 2009, World Health Organisation, Accessed 29-9-2010, [http://www.who.int/whosis/whostat/2009/en/index.html] Google Scholar

- Ferrinho P, Van Lerberghe WV, Fronteira I, Hipolito F, Biscaia A: Dual practice in the health sector: a review of the evidence. Human Resources for Health. 2004, 2: 14-10.1186/1478-4491-2-14. ArticlePubMedPubMed CentralGoogle Scholar

- Phyu YM, Chotbenjakul W: Medical tourism in Thailand and its impact on the internal brain drain of doctors. Submitted masters thesis. 2010, National University of Singapore, Lee Kuan Yew School of Public Policy Google Scholar

- Quek D: The Malaysian healthcare system: a review. Intensive workshop on health systems in transition: 29 - 30 April 2009; Kuala Lumpur. 2009, University of Malaya Google Scholar

- MOH Singapore: Health facts. 2008, Ministry of Health Singapore, Accessed 14-7-2010, [http://www.moh.gov.sg/mohcorp/statistics.aspx?id=5966] Google Scholar

- Ramesh M: Autonomy and control in public hospital reforms in Singapore. American Review of Public Administration. 2008, 38 (1): 62-79. 10.1177/0275074007301041. ArticleGoogle Scholar

Acknowledgements

All analysis and opinions expressed in this paper are the authors' alone. The authors acknowledge the insights on methodology provided by Wu Xun, as well as the detailed and helpful comments from Chee Heng Leng on an earlier version of this draft.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

- Lee Kuan Yew School of Public Policy, National University of Singapore, 469C Bukit Timah Road, OTH Building, Singapore, 259772, Singapore Nicola S Pocock & Kai Hong Phua

- Nicola S Pocock